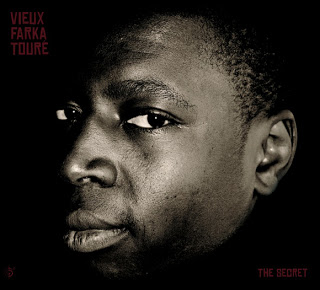

Interview with Vieux Farka Touré

The production story of Vieux Farka Touré’s The Secret begins on the death bed of his father. In the title track we have a previously unreleased session from the legendary Ali Farka Touré, recorded shortly before his admittance into hospital. Ali was to die of bone cancer a few days later. For one of the growing community of Malian blues fans the release of this session is hugely exciting; like many others, I skipped straight to track 7.

Ali’s typically dominant guitar loop has a meditative power over the listener. One is transported to a world of intense, life sapping heat; the pace of the track feels restricted by its control, and we are helpless to resist throughout its near 7 minute length. It’s a perfect final word from the master of the desert blues. In Vieux we have a son who is not trying to fill his father’s impossibly big shoes. He has used his legendary name to its full strength, bringing the desert blues to a globally connected world that Ali never lived to explore. Vieux continues to borrow from other cultures and musical genres effectively. At times his guitar has a sitar like twang; give him half the chance and he’ll break into a rock influenced solo. In this complex blend of cultures, what better way to bring clarity than to ask the man himself.

“I make the music, but whoever listens to it is the person who describes what they’re hearing,” says Vieux. “I tend to create music that incorporates elements of jazz, reggae, rock or maybe blues… it depends on who’s listening to it”

Would you compare your music to that of John Lee Hooker? I know your father saw him as an important source of inspiration over other American musicians.

I personally don’t compare myself to anyone, because I’m the only one doing it- I’m the only one making this kind of music. I know some people will always compare me to my father; that’s my birth right, and that will probably always be the case until the day I die. But I make my own music because I’m Vieux Farka Touré, and that’s what people will hear.

If you have this unique identity, would you consider it to be separate to other musicians in Mali? Is that music very different to the music you play?

It’s hard to answer that question because there are so many musicians in Bamako. I mix in all the music I like in creating my own sound.

Do you think music has a big role in Malian life for those who aren’t in the industry?

Musicians in Mali function as newspapers. We’re the ones who pass the information on, and we’re the ones who comment on what’s happening in social life, daily life and general evolution in terms of the country’s life. That’s what we give to the people.

Maybe music means a different thing here than to somebody from Mali. For me it’s just a form of entertainment but for you it’s much more integrated into the social network.

It’s true- a lot of people see music as you do, and it’s necessary. Without music to cheer up our lives, nothing goes right. But the fact is, there are so many people in Mali who don’t know how to read or write. People hear music live and on the radio. What they hear plays a role in education in terms of information, and so that is why my role is so important.

I remember I once read a quote from Ali saying he always put the land first and the music second. When recording in Niafunke, the sessions had to be fitted in between tending to his crops. Do you share this intimate relationship with the land?

You can’t make good music when you’re hungry. It’s as simple as that- you can’t contribute to the community if you’re hungry, and if the community lives without worrying about hunger then they can enjoy the music. This is the function that you were talking about earlier.

My feeling for the music would surely be different in Mali than to what I’ve just witnessed. Do you alter your set much to suit London or Bamako?

I think it’s obligatory that you have a different set list, because what my Malian audience requires and expects from me is so different from here. In general they tend to like my songs that are danceable. I tend to always do a set list- I put a list on and then I begin to feel what the audience really wants from me. And I’ll play more of that when I get the right vibe.

I guess that’s the same with any musician.

Exactly.

Leave a comment