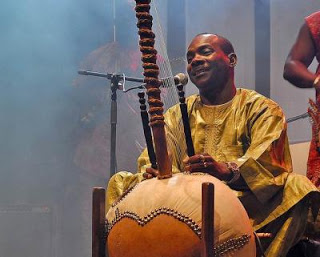

Interview with Toumani Diabaté

Griots usually come across as inherently modest. A non-griot can never become a griot, so underlying the respect given to his father, his grandfather and his teachers, every griot must feel eternally grateful to have been born at the end of such a lineage. Toumani Diabaté’s first words at The Royal Northern College of Music were unassuming- “I’m sorry, I don’t speak good English”- despite being quickly dispelled with an anecdote about his deep connection with Manchester.

This was Toumani’s first acknowledgement of his audience. He had entered head-bowed to a long applause, placed himself and his crutch on the floor- a childhood illness left Toumani with one leg paralysed- and started playing his kora without looking up. Perhaps, I’d thought after several well intertwined songs, he doesn’t want to break the flow of his instrument with conversation. Anyone who has been entranced by the powerful rise and fall of kora music can appreciate this mind set. When Toumani did address the audience, he expressed pride in his part in Mali’s Grammy Award winning collaboration- Diabaté and Ali Farka Touré’s In the Heart of the Moon– as undisputable evidence for his title as the greatest kora player in the world.

“It’s part luck, but fundamentally it’s the quality of what I do”, he told me afterwards. “My quality puts me ahead of other kora players.” It seems that even a griot-level of modesty cannot downplay Toumani’s achievements. He was keen to reflect on In the Heart of the Moon, evidently a hallowed product from his 20 year career.

“I played with Ali Farka Touré, but he is from the north of Mali and I am from the south. In the Heart of the Moon was the first time that people from the north and the south played together on an album. I’ve had a lot of collaboration in my life- Taj Mahal, Ketama- but the one with Ali was special. It was a gift from God to Mali.”

“We wanted to make the album sound soft because we both agreed that Malian music had been changed by a lot of aggressive styles- a lot of hip-hop- and people needed to look back into themselves. Where are we going? What are we doing? Now I feel that In the Heart of the Moon is more like a book than a CD. Every time you listen to it you hear something new… I hear this from a lot of people. They say, “Toumani, I can’t stop listening to it! Every time I listen, it’s like you’ve just made it today.” When I hear this reaction I am happy- I’ve always wanted to do an album like this.”

Was it your idea or Ali’s?

“It was really a collaboration between three people- Ali, myself and Nick Gold, the head of World Circuit. I had a key role because I was the first musician from Mali to live in the UK. I was on tour with Womad in 1987, but would always listen to musicians from Mali andSenegal in the car. By the time World Circuit travelled to Mali to look for Ali, and I had returned to Bamako. We met up, and I found Ali for them- I was the one who made the connection. Ali was recording Savane in his home with his band. This included Basekou Kouyate, Afel Bocoum, Mama Sissoko… many great people.”

“For three years, Ali had been trying to record a song called Kaira. He had tried with many musicians, but was never satisfied with the sound. Finally he said, “let’s go to Toumani.” So I took my kora and I went to the studio, and we did it in one take. Just one take. And Ali said…

(Toumani takes a deep sigh)

“This is exactly what I was looking for.” Then we played another song together, and five minutes later it was done. The next day I got a phone call from Nick asking if I wanted to record a duel album with Ali. I said “talk to Ali.” And Nick said “I’ve already talked to Ali, and he says to talk to you.” With that I said “yes, I’m positive.” So we recorded for two days- one hour on, one hour off- and then it was finished. No rehearsal.”

It’s amazing how the album works despite the guitar and the kora having such a different history.

“Ali’s style on guitar was different. Similarly, what I did tonight with Fanta Mady Kouyate was different. The electric guitar is a new thing in West Africa for griots, and we have found a special way to play it. It’s not like Hendrix or Clapton- we have transposed the sounds of our traditional instruments to the modern guitar. We have a special way to tune it, and the result has much more in common with our ancestral music than Western guitar styles.”

So you think there isn’t such a strong connection with America, Mali and blues music?

“World Circuit called it blues, but we have our own names. We’d never call it blues, that’s very much a Western invention. We call it djaro, djandjaro or poy- we have many different names. Blues in Mali means a doctor’s clothes; if you call for blues, someone will get you a doctor. We’ve shown that American blues music comes from West Africa, specifically Mali, but basically we have a different sound… and music from the south of Mali is distinctly different form the north.”

Leave a comment